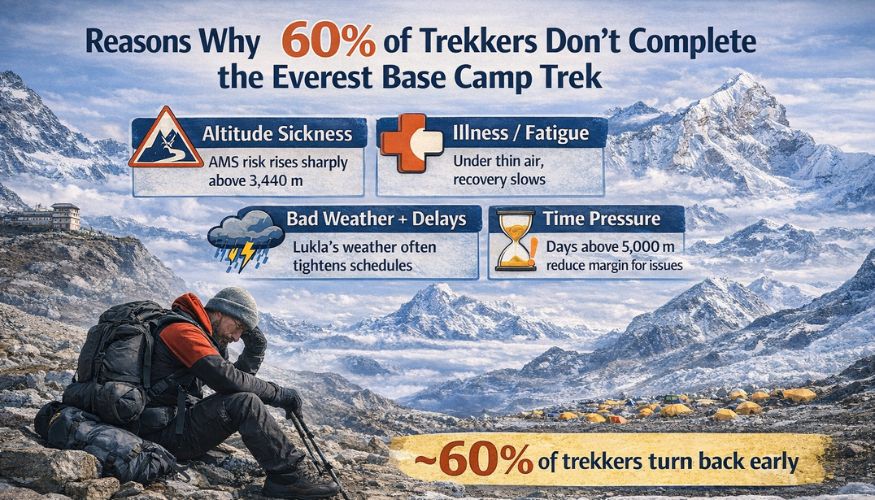

Reasons Why 60% Trekkers Fail to Complete the Everest Base Camp Trek

Around 60% of trekkers return before completing the Everest Base Camp trek. Sounds fascinating, right?

Most people don’t expect that number. Everest Base Camp looks achievable, well-marked, and widely trekked. There are teahouses, villages, and thousands of people attempting it every year. So when trekkers hear this for the first time, the next question usually comes immediately:

“If it’s not technical, why do so many people turn back?”

At Eco Nepal Trekkers, this number didn’t come from guesswork or marketing stories. It came from internal trekking records, post-trek interviews with our clients, and long conversations with our experienced guides, many of whom have been walking this route for over a decade.

And once we put all of that together, the answer became very clear.

People don’t fail Everest Base Camp because of courage, motivation, or fitness. They fail because high altitude changes how the body behaves, slowly at first, then very suddenly.

Quick Summary

- Around 60% of trekkers return early, based on Eco Nepal Trekkers’ internal data.

- Most unsuccessful attempts happen after several days on the trail, not at the start of the trek.

- Altitude sickness is the leading reason for turning back, affecting over half of trekkers in multiple studies.

- Illness, weather disruptions, flight delays, and rushed itineraries reduce safety margins at high altitude.

- Turning back is common, responsible, and often the safest decision on the Everest Base Camp trek.

An Important Clarification: Preparation Changes The Outcome Dramatically

One thing needs to be stated very clearly to avoid misunderstanding this data. The 60% return rate is not evenly distributed across all trekkers.

It is heavily concentrated among those who arrive underprepared, overconfident, or on rushed itineraries.

When we isolate trekkers who meet all of the following conditions:

- Follow a conservative acclimatization schedule

- Add proper rest days above Namche and Dingboche

- Respond immediately to early altitude symptoms

- Listen to guide decisions without pressure

- Maintain hydration, nutrition, and pacing discipline

The outcome changes completely.

Across well-prepared trekkers who follow guide advice strictly, completion rates is close to 95% in our internal records.

This higher success rate is not surprising. It aligns with what experienced guides observe season after season:

- Trekkers who respect altitude early rarely fail

- Trekkers who leave buffer days rarely run out of time

- Trekkers who descend at the first warning often recover and continue safely

In other words, Everest Base Camp is highly achievable for the prepared body and patient schedule.

The mountain does not randomly reject people. It exposes weaknesses in planning, pacing, and recovery.

That is why two numbers can be true at the same time:

- Around 60% of all attempts end early when you include rushed, underprepared, or inflexible itineraries

- Around 95% succeed when trekkers prepare properly and follow evidence-based acclimatization guidance

The difference is not strength or courage. The difference is the margin.

Where does this 60% Number Come From?

Before going further, it’s important to be honest about the data.

Nepal does not publish an official Everest Base Camp “completion rate.” National tourism statistics track how many people enter the Everest region, not how many reach Base Camp. For example, 52,499 foreign visitors entered Sagarmatha National Park in 2023, but that number includes everyone from short hikers to full EBC trekkers.

So our 60% non-completion figure comes from something else.

At Eco Nepal Trekkers, we reviewed:

- internal trek outcome records across multiple seasons

- post-trek interviews with trekkers who turned back

- Feedback from guides who made the decision to descend

- medical interruption points along the route

Then we compared those patterns with published medical studies, aid-post data, and documented weather and flight disruptions.

What we saw internally matched the external research almost perfectly.

Why do people think Everest Base Camp is easier than it really is?

This is where most misunderstandings begin.

Everest Base Camp is a non-technical trek. There are no ropes, no ice climbing, and no exposed ridgelines like on mountaineering routes. That creates a mental shortcut: “If it’s not technical, it must be manageable.”

And yes, trekking in Everest Base Camp isn’t that difficult, but the risk of altitude threats still remains.

In fact, our guides hear this often, especially from trekkers who have completed long hikes in Europe, Australia, or the United States.

But Everest Base Camp sits at 5,364 m, and that altitude quietly changes the rules.

Below 3,000 m, most people can walk, eat, sleep, and recover normally. Above 4,000 m, recovery slows. And above 5,000 m, even small problems stop being small.

That is the part most people underestimate before they arrive.

Altitude sickness is the main reason trekkers turn back

When we asked trekkers who didn’t finish why they stopped, one reason came up again and again: altitude sickness.

This matches medical research very closely.

A classic field study that followed 283 trekkers on the Everest Base Camp route day by day found that 57% developed Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) at some point during the trek. That is not an edge case. That is more than half.

What surprises many trekkers is not that AMS happens, but when it happens.

Most people feel fine early. They walk well to Namche. They enjoy the views. They sleep okay. Then, after several days at higher sleeping altitudes, symptoms appear quickly.

And here is the key point our guides explain clearly:

When AMS worsens, the correct response is to stop ascending and descend. There is no “pushing through” safely.

Once descent begins, most itineraries do not have enough buffer days to attempt Base Camp again. That is how many treks end early, even when motivation is high.

The altitude zone where most failures actually happen

Trekkers rarely fail in the first few days. Most failures happen after Dingboche, when altitude stops being gradual and starts being demanding.

Medical data support this observation.

A review of severe altitude illness cases at the Pheriche medical aid post by Wilderness Medical Society showed that 91% developed symptoms above the aid post, with a median onset altitude of about 4,834 m.

That number matters because it overlaps exactly with where trekkers attempt:

- Lobuche

- Gorak Shep

- Everest Base Camp

By this stage:

- Sleeping altitude is very high

- Appetite often drops

- Sleep becomes shallow

- hydration becomes harder

Many trekkers tell us the same thing during interviews:

“I felt strong until one day I didn’t.”

That shift is not psychological. It is physiological.

Medical interruptions are common, even if not everyone quits immediately

Another pattern we see often is interruption before failure.

A study of 366 Everest Base Camp trekkers found that 40.5% experienced at least one medical incident, and almost half of those incidents were related to AMS.

Not every medical incident ends a trek immediately. But once an itinerary slips at high altitude, the chance of completion drops quickly.

Our guides see this repeatedly. A single extra rest day near Lobuche can mean the difference between finishing and turning back due to time constraints.

What aid-post data quietly tells us

High-altitude aid posts tell the real story of where bodies struggle.

Comparative analysis of Himalayan aid posts showed:

- around 20% AMS diagnosis at the higher Pheriche aid post

- around 6% at the lower Manang aid post

| Aid post altitude | AMS diagnosis rate |

| Lower altitude (Manang) | 6% |

| Higher altitude (Pheriche) | 20% |

This difference is not about trail difficulty. It is about sleeping altitude combined with ascent speed.

That is why many trekkers stall or descend around Pheriche, Lobuche, or nearby villages.

Illness quietly ends many treks

Not all failures look dramatic.

In the 283-trekker EBC study, 87% experienced at least one infection-related symptom. Common issues included colds, cough, and sore throat.

At sea level, these are minor. At 4,500 to 5,000 m, they can seriously affect breathing, sleep, and energy.

During interviews, many trekkers who turned back did not describe a single big problem. They described accumulated fatigue, poor sleep, and a body that simply stopped recovering.

Gastrointestinal illness is underestimated but powerful

Another quiet but common factor is gastrointestinal illness.

That same study found 36% of trekkers experienced diarrhoea on the Everest Base Camp route.

At altitude, dehydration, weakness, and appetite loss compound rapidly. When the trek requires daily elevation gain, even one bad episode can derail the entire plan.

From our internal data, this is a frequent reason trekkers turn back despite feeling mentally ready to continue.

Weather forces decisions, not opinions

Some trekkers fail not because of their body, but because the mountain removes choice.

Heavy snowfall has repeatedly closed trekking routes in the Everest region, and severe conditions have even caused helicopter accidents during rescue attempts near Lobuche.

When visibility drops or ice builds rapidly, the decision is no longer personal. Turning back becomes the only safe option.

Our guides often explain this simply:

“The mountain decides before we do.”

Flight delays quietly end many treks

Time pressure is one of the least discussed failure reasons.

Documented periods of multi-day Lukla flight cancellations have stranded trekkers. When flights resume, surges of over 1,150 trekkers landing in Lukla show how quickly schedules compress.

Many trekkers operate on fixed international return flights. Losing several days to the weather often means choosing not to continue, even if health allows.

From the outside, it looks like failure. From the inside, it is logistics.

Severe cases force non-negotiable endings

Some treks end because they must.

The Himalayan Rescue Association’s Spring 2025 report from Pheriche recorded 399 patients , including severe cases requiring oxygen, medication, and immediate descent.

Once that threshold is crossed, completing Everest Base Camp is no longer relevant. Safety becomes the only goal.

Speed is the silent multiplier of failure

One pattern stands out clearly in both our internal data and regional reporting: rushed itineraries.

Reports have described days with up to about 100 helicopter flights, alongside concerns about fast, low-cost itineraries that reduce acclimatization time.

| Trek pacing | Outcome trend |

| Conservative pacing | Higher completion likelihood |

| Rushed ascent | Higher failure and evacuation risk |

Altitude does not reward speed. It penalises it. Which is why, if you haven’t been trekking, one should never rush the journey. In fact, if you have a time crunch, you can always go for the Everest view trek, as trekking itself isn’t that difficult, and you can get a clear view of Mount Everest as well.

What this really means for trekkers

So yes, around 60% of trekkers return before completing Everest Base Camp.

That number does not mean the trek is unsafe. It means high altitude reveals limits slowly, then decisively.

Most people who turn back are capable hikers. They are motivated. They prepare. But altitude changes the equation after several days, not on the first one.

At 5,364 m, success is not about toughness. It is about patience, pacing, and leaving margin.

That is what our guides explain on the trail. And that is what the data quietly confirms.

FAQs

Do most trekkers really fail to complete Everest Base Camp?

Based on Eco Nepal Trekkers’ internal data, around 60% return early. This is not an official national statistic.

Why is there no official completion rate?

Nepal tracks regional visitors, not Base Camp finishers. There is no public “finish line” dataset.

What is the main reason people fail?

Altitude sickness is the most common reason. Medical studies show it affects over half of trekkers.

At what point do most trekkers turn back?

Most turn back above Dingboche, near Lobuche or Pheriche. This is where altitude becomes unforgiving.

Do people fail because they are unfit?

Usually no. Most failures are physiological, not motivational.

Can an illness other than altitude sickness end a trek?

Yes. Respiratory infections and diarrhoea are common. At altitude, even mild illness can drain energy quickly.

Does the weather cause people to fail?

Yes. Heavy snowfall and poor visibility can close routes. When conditions worsen, turning back is mandatory.

How do flight delays affect completion?

Multi-day Lukla flight cancellations can consume buffer days. Many trekkers run out of time, not strength.

Do rushed itineraries increase failure rates?

Yes. Faster ascents reduce acclimatization time. This increases illness and evacuation risk.

Is failing to complete Everest Base Camp a bad thing?

No. Turning back is often the correct decision. Safe descent is always more important than reaching Base Camp.